Restoration planning

Contents

Constraints in identifying river rehabilitation project success

Little is known about the effectiveness of river restoration efforts despite the rapid increase in river restoration projects. Restoration outcomes are often not fully evaluated in terms of success or reasons for success or failure and this is, in part, due to weaknesses in the design and implementation stages of project planning for rehabilitation schemes. The review of concepts to measure the success of river restoration found that despite large economic investments in what has been called the “restoration economy”, many practitioners do not follow a systematic approach for planning restoration projects. As a result, many restoration efforts fail or fall short of their objectives, if objectives have been explicitly formulated. Some of the most common problems or reasons for failure include:

- Not addressing the root cause of habitat degradation

- Poor or improper project design, skipping key design steps

- Expectations not clearly defined with measurable objectives, therefore project success is difficult to evaluate through monitoring (Bernhardt et al. 2007)

- Not establishing reference condition benchmarks and success evaluation endpoints against which to measure success

- Failure to get adequate support from public and private organizations

- No or an inconsistent approach for sequencing or prioritizing projects (Roni et al. 2013)

- Inappropriate use of common restoration techniques because of lack of pre-planning (one size fits all) (Montgomery & Buffingtion 1997)

- Inadequate monitoring or appraisal of restoration projects to determine project effectiveness (Roni & Beechie 2013)

- Improper evaluation of project outcomes (real cost benefit analysis)

Figure 1. Success rate of 671 European case studies recorded from the REFORM WP1 database.

Figure 1. Success rate of 671 European case studies recorded from the REFORM WP1 database.

Benchmarking, Endpoints and project success

Overall, evaluating how successful restoration measures have been, as well as determining reasons for success or failure are essential if restoration measures are to meet obligations under the WFD. Setting benchmarks and end points that are linked to clearly defined project goals is considered the most appropriate approach to help measure of success (Buijse et al. 2005).

Benchmarking

Benchmarking as a tool should be feasible, practical and measureable to help guide future decision support tools. One of the first steps is to establish benchmark conditions against which to target restoration measures. Benchmarking uses representative sites otherwise known as ‘reference sites’ on a river that have the required ecological status and are relatively undisturbed; this is then used as a target for restoring other degraded sections of river within the same river or catchment. This requires:

- Assessment of catchment status and identifying restoration needs before selecting appropriate restoration actions to address those needs

- Identifying a prioritization strategy and prioritizing actions

- Developing a monitoring and evaluation programme

- Participation and fully consultation of stakeholders

Endpoints

It is imperative that endpoints accompany benchmarking in the planning process to guarantee the prospect of measuring success because endpoints are feasible targets for river rehabilitation. It is important to note that endpoints are different to benchmarks, this is because other demands on the river systems also have to be met and references can only function as a source of inspiration on which the development towards the endpoints is based (Buijse et al. 2005). Given that benchmark standards cannot always be achieved, especially on urban rivers, endpoints will therefore assist in moving restoration effort forward through application of the SMART approach, to decide what is achievable and what is feasible. There is a need to distinguish endpoints for:

- Individual measures

- Combination of measures

- Catchment water bodies

- River basin districts

Planning protocol for river restoration

With an increasing emphasis on river restoration comes a need for innovative tools and guidance to move decisions based largely on subjective judgments to those supported by scientific evidence (Boon & Raven 2012). The restoration planning protocol developed uses project management techniques to solve problems and produce a strategy for the execution of appropriate projects to meet specific environmental and social objectives (Figure 2). The procedure is process driven in its development and makes use of various project planning tools (e.g. PDCA, DPSIR, conflict resolution, environmental impact assessment and logical framework, SMART and participation ladders) to:

- Diagnose problems and produce a strategy for their remediation;

- Provide knowledge of the technical policy and background to conflicts of multiple use of resources;

- Develop a plan based on benchmarking and endpoints for setting specific and measurable targets with objectives as defined by the institutional, regional, national policy;

- Ultimately develop action plan with actions and targets, whilst recognising the need for an integrated approach to management of resources to minimise conflicts and optimise use.

Figure 2. Proposed planning protocol for restoration projects - yellow coloured boxes represent steps in the DPSIR approach to management intervention.

Projects should typically proceed through three main phases associated with the project cycle (e.g. Skidmore et al. 2011):

- Project identification: which establishes the purpose and need for restoration, puts the project in a watershed context, and articulates the specific intentions of a project

- Project formulation: which describes the details of the project and how it will be implemented and the project objectives accomplished

- Project Implementation & monitoring: which includes the actions taken to complete the project, checking to see that the project was implemented as designed, and evaluating whether the project had the desired habitat and biological effects.

Table 1 (File:WP5 1Table 1.pdf) contains an overview of steps on the planning protocol outlined in Figure 2.

Project identification

Project identification is the stage at which the initial restoration project proposal is conceived and formulated. The identification phase may be divided into two fundamental aspects. In the first the restoration project concept is considered in relation to:

- The overall status of the aquatic ecosystem functioning and the ecological status or potential;

- The regional or national policy and WFD priorities (see - http://www.restorerivers.eu/Publications/tabid/2624/mod/11083/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/3052/Default.aspx).

The first step provides an understanding of the current status of the ecosystem functioning and ecosystem services in the management zone to establish the baseline against which to develop any restoration project (equivalent to the DPSIR State assessment). The basic information required includes, but is not exclusive to:

- Background geography and landscape topography, political domains, climate and general infrastructural development;

- Habitat modification and geomorphological alteration;

- Hydrology, including modifications to flow regulation, abstraction and other water uses;

- Flood defence;

- Fisheries, recreation and conservation;

- Water quality;

- Land use/navigation and mineral extraction;

- Urban, agricultural and industrial development.

In the second aspect of the identification phase the relevant policy issues are considered, notably:

- The overall justification for the project (perspectives, development objectives);

- The likely target groups and impact beneficiaries, as well as those who might be adversely affected;

- The key factors influencing the likely success and failure of the project.

Restoration objectives should be clearly defined adopting a river basin-wide approach, and have been developed from high priority WFD and national policy objectives (equivalent to the DPSIR Drivers assessment). This intrinsically moves the existing approach from being issue-driven towards an emphasis on forward planning. Typical WFD policy objectives include:

- Achievement of GES or GEP;

- Conservation & efficient exploitation of resources;

- Contribution to species conservation objectives;

- Creation of regional employment and maximising social benefits;

- Regional development (regional and multi-lateral cooperation);

- Establishment of the legal and administrative framework for regulation;

- Assessment of environmental, economic and social impacts;

- Maximising ecosystem health.

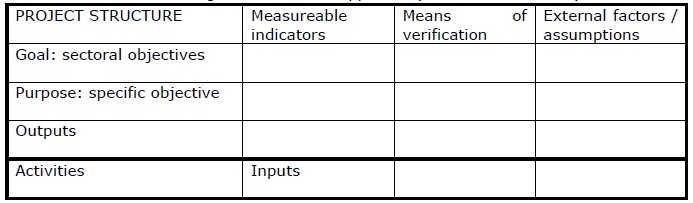

The third aspect concentrates on the techniques used to measure the viability of the restoration project as it evolves through the phases of the project approach. One of the most commonly used techniques to structure the process described above is the logical framework approach (Anon 1982; Table 2). The technique is useful in setting out the design of the restoration project in a clear and logical way so that any weaknesses that exist can be brought to the attention of the planners. Starting with the aim of the project, a series of objectives, outputs and inputs are developed down the first column at the left-hand side of the page. The second column addresses the indicators (endpoints) that have been determined at the outset of the project and how they can be verified as the project is developed further through the various phases of the project approach. The final column assesses the risks and assumptions which underpin the elements described in the first two columns. As the restoration project develops the logical framework will be modified to take account of new information likely to affect the project elements. Any deficiencies may then be remedied at an early stage, or if insuperable, the restoration project may be discounted. The logical framework technique emphasises the value of choosing measurable indicators or endpoints which can be assessed throughout the life of the project, and also instructs the planners to assess carefully the risks and assumptions upon which the project is based.

Table 2: Form of the Logical Framework Approach (source: Anon. 1982)

fdfdfdfdfdfdf