Difference between revisions of "Category:Hydromorphological models"

(→2. Which types of models can be distinguished?) |

(→How to deal with different scales?) |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Hydromorphological models are useful tools for assessing how a river works. This page provides access to general aspects of modelling as well as a set of factsheets on specific types of models.'''<br /> | '''Hydromorphological models are useful tools for assessing how a river works. This page provides access to general aspects of modelling as well as a set of factsheets on specific types of models.'''<br /> | ||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == What is a model? == |

A model is a representation of aspects of reality for a specific purpose. Hence it is not a replica of reality. Models occur in a wide variety, from simple descriptions (word models) to complex three-dimensional computer models. In a general sense, everybody thus uses models. In a more restricted operational sense, however, the term “models” usually refers to mathematical models that run on computers. | A model is a representation of aspects of reality for a specific purpose. Hence it is not a replica of reality. Models occur in a wide variety, from simple descriptions (word models) to complex three-dimensional computer models. In a general sense, everybody thus uses models. In a more restricted operational sense, however, the term “models” usually refers to mathematical models that run on computers. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Which types of models can be distinguished?== |

As models occur in a wide variety, it is useful to distinguish different types, see figure. | As models occur in a wide variety, it is useful to distinguish different types, see figure. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 20: | ||

The true picture is nonetheless more complex. Physics-based hydromorphological models include empirical elements too, such as predictors for hydraulic resistance or sediment transport. Empirical models can also result in complex computer models, for instance if they are based on neural networks. The subdivision presented here serves only as general guidance, without including all the subtleties of advanced or hybrid forms. | The true picture is nonetheless more complex. Physics-based hydromorphological models include empirical elements too, such as predictors for hydraulic resistance or sediment transport. Empirical models can also result in complex computer models, for instance if they are based on neural networks. The subdivision presented here serves only as general guidance, without including all the subtleties of advanced or hybrid forms. | ||

| − | == | + | ==What is the use of numerical models in river restoration?== |

The term “models” usually refers to numerical models, based on mathematical equations and running on computers. They can be used for various purposes in river restoration: | The term “models” usually refers to numerical models, based on mathematical equations and running on computers. They can be used for various purposes in river restoration: | ||

| − | + | * Integration of knowledge on a river in a structured database | |

| − | + | * Assessment of a hydromorphological state, enhancing the information from field measurements (“clever interpolation”) | |

| − | + | * Identification of data requirements for monitoring or measurement campaigns | |

| − | + | * Evaluation of the effect of pressures | |

| − | + | * Evaluation of the effect of restoration measures | |

| − | + | * Evaluation of the effect of scenarios such as scenarios of climate change | |

| − | + | * Establishment of design conditions for restoration measures | |

| − | + | * Analysis of the sensitivity around tipping points such as the transition between meandering and braiding | |

| − | + | * Scientific research and testing of hypotheses, for instance about how hydromorphology interacts with the development of vegetation | |

| − | + | * Communication, as a tool for explanation and a basis for discussion | |

The usefulness of numerical modelling in a particular case depends on the needs to meet these purposes, not on data availability. A lack of data is almost never a valid reason to abstain from modelling. | The usefulness of numerical modelling in a particular case depends on the needs to meet these purposes, not on data availability. A lack of data is almost never a valid reason to abstain from modelling. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Who can use numerical models?== |

The use of numerical models requires background knowledge and training. Staff of river management authorities can feasibly meet these requirements for the simpler numerical models, but usually needs to contract out the application of more complex numerical models. A precise distinction is hard to give. One-dimensional (1D) hydrodynamic models are usually routine tools for management authorities, whereas two-dimensional depth-averaged (2DH) or three-dimensional (3D) morphodynamic models commonly require the involvement of specialized modellers. Most restoration projects do not need 2DH or 3D morphodynamic models. These models are important tools, however, when restoration interferes with navigation. | The use of numerical models requires background knowledge and training. Staff of river management authorities can feasibly meet these requirements for the simpler numerical models, but usually needs to contract out the application of more complex numerical models. A precise distinction is hard to give. One-dimensional (1D) hydrodynamic models are usually routine tools for management authorities, whereas two-dimensional depth-averaged (2DH) or three-dimensional (3D) morphodynamic models commonly require the involvement of specialized modellers. Most restoration projects do not need 2DH or 3D morphodynamic models. These models are important tools, however, when restoration interferes with navigation. | ||

| − | == | + | ==What is the use of analytical models in river restoration?== |

One might question the use of analytical models based on simplified equations for physical processes if numerical models are available with a more complete representation of physical processes. However, analytical models provide convenient tools for rapid assessment and rules of thumb. This is the main utility of analytical models in river restoration. | One might question the use of analytical models based on simplified equations for physical processes if numerical models are available with a more complete representation of physical processes. However, analytical models provide convenient tools for rapid assessment and rules of thumb. This is the main utility of analytical models in river restoration. | ||

It is worth noting, however, that analytical models are also important for the numerical models used in river restoration. Analytical solutions of mathematical equations are complementary to numerical solutions, as they offer additional insights into the fundamental behaviour of the corresponding physical system. Designing numerical models requires analytical models to determine the appropriate numerical scheme and the type and location of the boundary conditions to be imposed. Analytical models also help the optimization of calibration strategies for numerical models, as they reveal which parameters are responsible for different aspects of the solution. They help the interpretation of results from numerical models as well, because numerical solutions may exhibit spurious wiggles, phase lags or attenuation that in this way can be distinguished from real physical phenomena. Finally, analytical solutions provide exact solutions for certain idealized cases that may serve as validation cases for numerical models. | It is worth noting, however, that analytical models are also important for the numerical models used in river restoration. Analytical solutions of mathematical equations are complementary to numerical solutions, as they offer additional insights into the fundamental behaviour of the corresponding physical system. Designing numerical models requires analytical models to determine the appropriate numerical scheme and the type and location of the boundary conditions to be imposed. Analytical models also help the optimization of calibration strategies for numerical models, as they reveal which parameters are responsible for different aspects of the solution. They help the interpretation of results from numerical models as well, because numerical solutions may exhibit spurious wiggles, phase lags or attenuation that in this way can be distinguished from real physical phenomena. Finally, analytical solutions provide exact solutions for certain idealized cases that may serve as validation cases for numerical models. | ||

| − | == | + | ==How to deal with different scales?== |

That models deal with aspects of reality rather than full reality is closely related to scale. On the scale of meander bends and floodplains, models do not represent the details of ripples on the river bed. Ripples are then merely noise represented by averaged quantities such as average bed level and hydraulic resistance (parameterization). On the scale of detailed flow patterns and sediment transport around ripples and dunes on the river bed, the overall picture of the river basin is less important. Influences from far away are captured in the boundary conditions for a local area. | That models deal with aspects of reality rather than full reality is closely related to scale. On the scale of meander bends and floodplains, models do not represent the details of ripples on the river bed. Ripples are then merely noise represented by averaged quantities such as average bed level and hydraulic resistance (parameterization). On the scale of detailed flow patterns and sediment transport around ripples and dunes on the river bed, the overall picture of the river basin is less important. Influences from far away are captured in the boundary conditions for a local area. | ||

| − | The scale under consideration determines the level of detail and the appropriate modelling approach. For hydromorphological models, scales are defined in another way than for hydromorphological assessment. They are based on relative space scales of morphological features for hydromorphological models, but on partly absolute space scales of areas considered for hydromorphological assessment. As a result, the space scale quoted for the same area and morphological features is smaller for hydromorphological models than for hydromorphological assessment. The table below shows a comparison. Note that the term “reach” refers to different scales in the two systems. | + | The scale under consideration determines the level of detail and the appropriate modelling approach. For hydromorphological models, scales are defined in another way than for hydromorphological assessment ([https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53199-5.00033-6 Wright & Crosato (2011))]. They are based on relative space scales of morphological features for hydromorphological models, but on partly absolute space scales of areas considered for hydromorphological assessment. As a result, the space scale quoted for the same area and morphological features is smaller for hydromorphological models than for hydromorphological assessment. The table below shows a comparison. Note that the term “reach” refers to different scales in the two systems. |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | {| | + | {|border="1" style="border-collapse:collapse" |

| align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''Hydromorphological assessment''' | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''Hydromorphological assessment''' | ||

| − | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''''' | + | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''Indicative space scale''' |

| align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''Hydromorphological models''' | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''Hydromorphological models''' | ||

| − | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''''' | + | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''Relative space scale''' |

| − | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''''' | + | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''Morphological features''' |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | catchment|| | + | | [[Catchment | catchment]]||10<sup>2</sup> – 10<sup>4</sup> km<sup>2</sup>||river basin||river basin||sediment yield |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | landscape unit|| | + | | [[Landscape_unit | landscape unit]]||10<sup>2</sup> – 10<sup>3</sup> km<sup>2</sup>||-||-||- |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | segment||10 – 100 km||reach||depth divided by slope||longitudinal profile | + | |[[Segment | segment]]||10 – 100 km||reach||depth divided by slope||longitudinal profile |

|- | |- | ||

| ||||corridor||valley width, floodplain width||floodplains, oxbow lakes, meander bends | | ||||corridor||valley width, floodplain width||floodplains, oxbow lakes, meander bends | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | reach||0.1 – 10 km||cross-section||main-channel width, active width||bars, channels, pools | + | | [[Reach | reach]]||0.1 – 10 km; (>20 widths)||cross-section||main-channel width, active width||bars, channels, pools |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | ||( | + | | [[Geomorphic_unit |geomorphic unit]]||1 – 100 m; (0.1 – 20 widths)||depth||flow depth||bedforms, dunes, scour holes |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | [[Hydraulic_unit |hydraulic unit]]||0.1 – 10 m||process||sediment grain size, thickness of viscous sublayer||ripples |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | [[River_element | river element]]||0.01 – 0.1 m|||||| |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | | river element||0.01 – 0.1 m|||||| | + | |

|} | |} | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| Line 85: | Line 78: | ||

The depth and process scales are realms of scientific research on elementary processes and their interactions. The corridor and cross-section scales are appropriate for analysis of ecosystem degradation, design of river restoration projects, assessment of habitat diversity, and assessment of the sustainability of restoration. The river basin and reach scales are appropriate for analysis of ecosystem degradation and assessment of the sustainability of restoration too, and also for large-scale and long-term impact assessment of restoration. | The depth and process scales are realms of scientific research on elementary processes and their interactions. The corridor and cross-section scales are appropriate for analysis of ecosystem degradation, design of river restoration projects, assessment of habitat diversity, and assessment of the sustainability of restoration. The river basin and reach scales are appropriate for analysis of ecosystem degradation and assessment of the sustainability of restoration too, and also for large-scale and long-term impact assessment of restoration. | ||

| − | + | ==Which models are presented in the REFORM wiki?== | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | == | + | |

The REFORM wiki contains factsheets of the following hydromorphological models: | The REFORM wiki contains factsheets of the following hydromorphological models: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

[[Category:Tools]] | [[Category:Tools]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:29, 7 January 2019

Hydromorphological models are useful tools for assessing how a river works. This page provides access to general aspects of modelling as well as a set of factsheets on specific types of models.

Contents

- 1 What is a model?

- 2 Which types of models can be distinguished?

- 3 What is the use of numerical models in river restoration?

- 4 Who can use numerical models?

- 5 What is the use of analytical models in river restoration?

- 6 How to deal with different scales?

- 7 Which models are presented in the REFORM wiki?

What is a model?

A model is a representation of aspects of reality for a specific purpose. Hence it is not a replica of reality. Models occur in a wide variety, from simple descriptions (word models) to complex three-dimensional computer models. In a general sense, everybody thus uses models. In a more restricted operational sense, however, the term “models” usually refers to mathematical models that run on computers.

Which types of models can be distinguished?

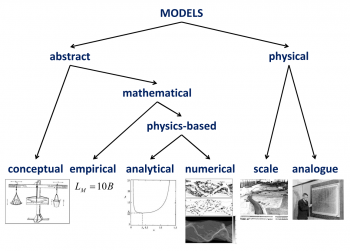

As models occur in a wide variety, it is useful to distinguish different types, see figure.

Models can be divided into abstract models (models you cannot touch) and physical models (models you can touch). Abstract models can be divided into conceptual models, such as word models and graphical representations, and mathematical models, based on mathematical formulas or equations. Deriving these formulas or equations from data leads to empirical models (induction or data-oriented approach). Deriving them from general principles leads to theoretical models (deduction). The latter are called “physics-based” if general laws of physics are used for the general principles (process-oriented or mechanistic approach). Some controversial models in hydromorphology use non-physics-based principles such as minimum energy dissipation or maximum sediment transport, but those models are not generally accepted.

The equations of mathematical models can be solved in two ways. One way is that they are simplified to an amenable form for analysis. This leads to analytical models. The other way is that they are translated into a form that can be solved by a computer. This leads to numerical models.

Rules of thumb are simple, easy-to-use quantitative models. They are derived from empirical or analytical models.

Physical models can be divided into scale models and analogue models. Scale models are models constructed at a reduced scale, similar to miniature parks. Scale laws and scale rules translate measurements in the model to values in the real world. Analogue models were used in the past, based on analogies between different physical systems. For instance, currents in an electrical circuit are similar to currents in a river network. Amperes and volts in the electrical circuit thus provided information on discharges and water levels in the corresponding river network.

The true picture is nonetheless more complex. Physics-based hydromorphological models include empirical elements too, such as predictors for hydraulic resistance or sediment transport. Empirical models can also result in complex computer models, for instance if they are based on neural networks. The subdivision presented here serves only as general guidance, without including all the subtleties of advanced or hybrid forms.

What is the use of numerical models in river restoration?

The term “models” usually refers to numerical models, based on mathematical equations and running on computers. They can be used for various purposes in river restoration:

- Integration of knowledge on a river in a structured database

- Assessment of a hydromorphological state, enhancing the information from field measurements (“clever interpolation”)

- Identification of data requirements for monitoring or measurement campaigns

- Evaluation of the effect of pressures

- Evaluation of the effect of restoration measures

- Evaluation of the effect of scenarios such as scenarios of climate change

- Establishment of design conditions for restoration measures

- Analysis of the sensitivity around tipping points such as the transition between meandering and braiding

- Scientific research and testing of hypotheses, for instance about how hydromorphology interacts with the development of vegetation

- Communication, as a tool for explanation and a basis for discussion

The usefulness of numerical modelling in a particular case depends on the needs to meet these purposes, not on data availability. A lack of data is almost never a valid reason to abstain from modelling.

Who can use numerical models?

The use of numerical models requires background knowledge and training. Staff of river management authorities can feasibly meet these requirements for the simpler numerical models, but usually needs to contract out the application of more complex numerical models. A precise distinction is hard to give. One-dimensional (1D) hydrodynamic models are usually routine tools for management authorities, whereas two-dimensional depth-averaged (2DH) or three-dimensional (3D) morphodynamic models commonly require the involvement of specialized modellers. Most restoration projects do not need 2DH or 3D morphodynamic models. These models are important tools, however, when restoration interferes with navigation.

What is the use of analytical models in river restoration?

One might question the use of analytical models based on simplified equations for physical processes if numerical models are available with a more complete representation of physical processes. However, analytical models provide convenient tools for rapid assessment and rules of thumb. This is the main utility of analytical models in river restoration.

It is worth noting, however, that analytical models are also important for the numerical models used in river restoration. Analytical solutions of mathematical equations are complementary to numerical solutions, as they offer additional insights into the fundamental behaviour of the corresponding physical system. Designing numerical models requires analytical models to determine the appropriate numerical scheme and the type and location of the boundary conditions to be imposed. Analytical models also help the optimization of calibration strategies for numerical models, as they reveal which parameters are responsible for different aspects of the solution. They help the interpretation of results from numerical models as well, because numerical solutions may exhibit spurious wiggles, phase lags or attenuation that in this way can be distinguished from real physical phenomena. Finally, analytical solutions provide exact solutions for certain idealized cases that may serve as validation cases for numerical models.

How to deal with different scales?

That models deal with aspects of reality rather than full reality is closely related to scale. On the scale of meander bends and floodplains, models do not represent the details of ripples on the river bed. Ripples are then merely noise represented by averaged quantities such as average bed level and hydraulic resistance (parameterization). On the scale of detailed flow patterns and sediment transport around ripples and dunes on the river bed, the overall picture of the river basin is less important. Influences from far away are captured in the boundary conditions for a local area.

The scale under consideration determines the level of detail and the appropriate modelling approach. For hydromorphological models, scales are defined in another way than for hydromorphological assessment (Wright & Crosato (2011)). They are based on relative space scales of morphological features for hydromorphological models, but on partly absolute space scales of areas considered for hydromorphological assessment. As a result, the space scale quoted for the same area and morphological features is smaller for hydromorphological models than for hydromorphological assessment. The table below shows a comparison. Note that the term “reach” refers to different scales in the two systems.

| Hydromorphological assessment | Indicative space scale | Hydromorphological models | Relative space scale | Morphological features |

| catchment | 102 – 104 km2 | river basin | river basin | sediment yield |

| landscape unit | 102 – 103 km2 | - | - | - |

| segment | 10 – 100 km | reach | depth divided by slope | longitudinal profile |

| corridor | valley width, floodplain width | floodplains, oxbow lakes, meander bends | ||

| reach | 0.1 – 10 km; (>20 widths) | cross-section | main-channel width, active width | bars, channels, pools |

| geomorphic unit | 1 – 100 m; (0.1 – 20 widths) | depth | flow depth | bedforms, dunes, scour holes |

| hydraulic unit | 0.1 – 10 m | process | sediment grain size, thickness of viscous sublayer | ripples |

| river element | 0.01 – 0.1 m |

The depth and process scales are realms of scientific research on elementary processes and their interactions. The corridor and cross-section scales are appropriate for analysis of ecosystem degradation, design of river restoration projects, assessment of habitat diversity, and assessment of the sustainability of restoration. The river basin and reach scales are appropriate for analysis of ecosystem degradation and assessment of the sustainability of restoration too, and also for large-scale and long-term impact assessment of restoration.

Which models are presented in the REFORM wiki?

The REFORM wiki contains factsheets of the following hydromorphological models:

Pages in category "Hydromorphological models"

The following 18 pages are in this category, out of 18 total.